Flashguns -

How they work and the types of flashguns available

Before we begin a few notes on how electronic flashguns work.

All flashguns use a glass tube filled with an inert gas called Xenon (pronounced Zenon). Xenon is used as the light it emits is the same colour as daylight.

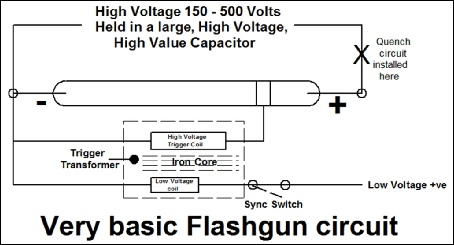

The circuit diagram below is only to show the basic concept, the real, practical, circuit is a lot more complicated than this.

Basic circuit operation Referring to Fig 1.

The high voltage capacitor is charged to a high voltage putting a potential of several hundred Volts across the Xenon tube.

A lower voltage is applied to the low voltage coil which generates a magnetic field in the iron core in the trigger transformer.

When the sync switch is opened (shown dotted) the low voltage disappears and the magnetic field generated by the low voltage coil in the iron core collapses through the high voltage coil which has thousands of turns of very fine wire.

This generates a very high voltage pulse (>20,000 Volts) which is applied to a metal ring around the Xenon tube, this very high voltage ionises the xenon gas within the tube which then conducts and the high voltage capacitor discharges through the gas in the tube. This excites the gas which emits a very bright light, and not a little heat, till the capacitor is exhausted, the xenon gas ceases to be conductive allowing the capacitor to recharge to a high voltage again. Note that there isn’t a ‘spark’ within the tube the light is emitted purely by the gas absorbing the energy from the capacitor.

As we can’t turn down the light level the Xenon tube emits we control the duration of the flash with a quench circuit, this removes the voltage from the tube before the capacitor is fully discharged, modern circuits save the remaining energy so the recycling time is faster.

The sync switch is controlled by another circuit so that the trigger voltage the

camera sees is low. Usually around 2 -

IMPORTANT WARNING

Older flashguns had trigger voltages derived from the main capacitor and not electronically controlled, these are dangerously high for modern cameras and would certainly blow their sync circuits, if not the whole circuit board, the use of old flashguns comes with this warning.

There are many old flashguns that appear in the second hand market that look a bargain, be warned they can blow your cameras electronics, their trigger voltages should always be measured before you connect them to your camera.

Small flashguns can be just as lethal to your camera as large ones.

You have been warned.

Types of Flashgun

There are 4 main types of flashguns

- Manual With these the output power is controlled manually by controlling the quench circuit. There has been a proliferation of manufacturers making these units recently, they have the advantage of being cheap and work well.

The quench control circuit is just a fast variable timer on full power they will be set to around 1/800th of a second after the trigger pulse, so the tube fires and 1/800th of a second later is quenched, for lower output this timer gets faster at very low powers (some units go as low as 1/256th of full output) it can be as fast as 1/50000th of a second, this is fast enough to freeze most any action.

- Auto The auto flashguns have a sensor, usually a photo transistor built into the flash, to determine when a set amount of light has been emitted and reflected off the subject, this usually corresponds to f8 on your camera, in other words they emit the same amount of light onto your subject no matter how far the flash is from the subject. I don’t know of any current manufacturer making these units, they were popular in the 1970’s to 1990’s due to their low price, the above warning applies.

- TTL These use a sensor in the camera and read the light reflected off the subject falling onto the sensor, hence TTL which stands for Through the Lens.

The huge advantage is that the camera sends a signal to the flashguns quench circuit when enough light has been received using the settings in the camera, so you will get a good exposure using any aperture, and shutter speed within limits (See X speed).

- Slave Flash These do not connect to the camera, they are triggered by a flashgun which is synced to the camera and with very cheap models usually have no control over power settings. Most of the more expensive flashguns have this mode too when output power can be controlled manually. Some TTL flashguns even maintain the TTL signalling between a master flash, mounted on the camera, and the slave(s). All flashguns in the lighting set up are then included in this measurement and you still keep auto flash.

The X speed

With a DSLR cameras you can’t use flash at any shutter speed. These have their shutter directly in front of the sensor and work by releasing the first curtain which uncovers the sensor then releasing the second curtain to cover the sensor back up again controlled by the shutter speed timer.

The problem is that to get fast shutter speeds they have to release the second curtain before the first curtain has reached the bottom of the sensor, if the flash goes off some of the light from the flashgun is masked by the first curtain and you will have a darker band on the part of your image that doesn’t see the flash.

The fastest shutter speed where all the sensor is uncovered is called the ‘X’ speed. This X speed can be anything from 1/160th of a second to 1/250th of a second depending on which manufacturer made your camera. This X speed will be in your camera’s specification.

Home : Using Flash : Manual Flash

Fig. 1

Guide Numbers (GN) You will usually see a Guide number associated with any flashgun, it’s supposed to be a measure of power, but, unfortunately, different manufacturers use different parameters, so it’s virtually impossible to compare two flashguns from different manufacturers directly using the GN number. There is an International ISO standard, but manufacturers rarely use it.

The ISO standard is the range in Meters of the flash when used at an ISO of 100 and the zoom set (if any) to 35mm.

American manufacturers and stockist's tend to quote the distance in feet rather than Meters then the GN is more than 3 times higher. This means that a flash with a GN of 100 in the USA is actually less powerful than a flash with a GN number of 50 internationally.

Manufacturers often quote the GN number when the flash is zoomed to the maximum which concentrates the light into a smaller area. This means the GN number is larger than it should be.

All this means you take GN numbers with a large measure of scepticism.

All you can say is that a flash with a GN number of 20 or less is not very powerful, your pop up flash will usually fall into this category, whilst a flash with a guide number of 60 is three times more powerful, don’t forget that 3 times more powerful is only 3 stops, compared to Sunlight flashguns are puny.

A note for any American visitors, first of all Welcome. The term ‘Flashgun’ or just ‘Flash’ is used throughout these articles, in UK English the term Strobe refers to a different kind of unit based on the same technology, a Strobe in the UK means a unit that emits a continuous stream of flashes, usually used for ‘freezing’ mechanical movement, a timing light for petrol engines is one example, but you find them in engineering and even Discos too.

There are flashguns that have this ability too, and can send out a stream of flashes within the same frame.